I thought a lot about resilience last year, during a six-week sabbatical bike ride through the Southwest. I covered a little over 1,900 miles, most of it over land that hadn’t seen a drop of rain since the previous fall; some of those areas—mostly in Texas—still hadn’t received significant precipitation months after my return home. Some farmers in Texas had to plow their cotton under or slaughter their cattle.

This year, Texas isn’t quite as dry, but much of the rest of the West and Midwest is in worse shape. This week an unprecedented 85% of the U.S. corn crop affected by drought along with 83% of soybeans, 71% of cattle pasture, and 63% of hay, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

Meanwhile, the Amtrak train that I was going to take home from Houston at the end of my bike trip last year was cancelled due to extensive flooding in the Upper Midwest. And back in Vermont, at the end of August (a year ago), we saw whole towns cut off by flooding and washed-out bridges and roads from Tropical Storm Irene. An early snow storm two months later caused power outages in Connecticut and Massachusetts that lasted up to a week-and-a-half.

Welcome to climate change.

Climate scientists tell us that we can expect more of these sorts of problems in the years and decades ahead. Precipitation patterns will become more variable, and more of our total precipitation will be bunched into intense deluges that run off as stormwater causing floods, rather than soaking into the ground to recharge aquifers.

While precipitation levels will increase overall due to climate change (because more water will be evaporated from the oceans and other bodies of water), some regions will become more drought-prone—including much of the western U.S.

Drought can cause power outages

We usually think of drought affecting agriculture or inconveniencing us by prohibiting lawn watering or washing our cars, but severe droughts will also impact our electricity grid. Roughly 89% of our electricity in the U.S. is produced with thermo-electric power plants that rely on huge quantities of cooling water. In 2007, severe drought in the southeastern U.S. resulted in one Tennessee Valley Authority nuclear plant being shut down and the output of two others reduced due to shortages of cooling water. And during the severe 2003 drought in Europe, 17 power plants in France and three in Germany were either shut down or their output reduced.

If the current drought facing the nation continues into the winter, we could well face a situation where dozens of power plants have to be shut down, reducing the margin of excess capacity—and raising the risk of brownouts and rolling blackouts.

There’s also terrorism to worry about

While we are now experiencing the first effects of a changing climate, we also face other threats and vulnerabilities. Terrorism is now an ever-present reality, and terrorists of the future may well target our energy production and distribution systems. The U.S. has 160,000 miles of high-voltage electricity distribution lines, 3,400 power plants, 2.5 million miles of natural gas and oil pipelines, and 150 oil refineries (nearly half located on the Gulf Coast). These installations could be targeted by terrorists wanting to harm the U.S. economy or our wellbeing.

While these systems are vulnerable to direct terrorist attack, even more scary is the threat of cyberterrorism, in which terrorists hack into the controls of energy production or distribution systems. In 2007, researchers at Idaho National Laboratory testing the vulnerability of power generation systems to computer attack, were able to hack into the controls of a generator and get it to self-destruct. Dubbed the Aurora Test, you can see the results in a video declassified by the Department of Homeland Security as the hacked generator shakes violently and begin smoking as it self-destructs.

And don’t forget solar flares

Yet another vulnerability is magnetic interference caused by coronal discharges from the sun (solar flares). These are the events that cause Aurora borealis or Northern Lights. According to an alarming 2008 report by the National Academy of Sciences, if we were to experience today a coronal discharge event as intense as one that occurred in 1859, tremendous damage could be done to our electrical grid—destroying transformers and causing power outages that could last months or even years. During the 1859 event, Northern Lights were seen as far south as Cuba and telegraph wires caught on fire!

Since the NAS report came out, the utility industry has awakened to this concern and begun modifying electrical systems to make them more robust, but the concern is still very real, according to experts.

Resilient design

It is this sort of vulnerability that I thought about during my bike trip and during the remainder of my sabbatical when I was back home. And it is this sort of thinking that led to the formation of the Resilient Design Institute.

It turns out that many of the strategies needed to achieve resilience—such as really well-insulated homes that will keep their occupants safe if the power goes out or interruptions in heating fuel occur—are exactly the same strategies we have been promoting for years in the green building movement. The solutions are largely the same, but the motivation is one of life-safety, rather than simply doing the right thing. We need to practice green building, because it will keep us safe—a powerful motivation, and this may be the way to finely achieve widespread adoption of such measures.

In this series of initial blogs, I’ll describe how we can address this vulnerability with more resilient homes and communities. Achieving such resilience won’t be easy and it will require investment, but I believe it is crucial for our future wellbeing.

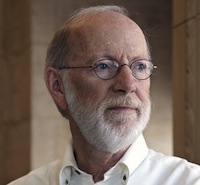

Alex Wilson is the founder of the Resilient Design Institute in Brattleboro, Vermont, a nonprofit organization committed to advancing practical solutions that can be employed by communities, businesses, and individuals to adapt and thrive amid the accelerating social, ecological, and climatological change being experienced today. He is also the founder of BuildingGreen, Inc. in Brattleboro and executive editor of Environmental Building News.